When you purchase through links on our site, we may earn an affiliate commission. Here’s how it works. |

OpticalLimits has recently gotten its hands on the Canon RF 14-35mm f/4L IS USM, which was announced way back on June 29, 2021. That in itself probably isn’t newsworthy. So instead of talking about the review itself, I focused on a specific part of the review that caught my eye. This part of the review was the MTF results before and after digital correction.

Many of you know that when I review Canon patents, I usually whine if Canon has an image circle that is less than the full frame coverage. This means that the camera has to “stretch” the image circle to fit the entire frame. From a purist point of view, this means we are relying on software versus optics. And I know, with almost every single lens release, this is a hotly debated topic.

Canon Didn’t Do This Before (as much)

This, of course, was never really something that Canon considered before the mirrorless era, not because they have gotten lazy in this era. The reason is that it was never a good option with optical viewfinders, because the distortion would be visible as you are composing your shot. With mirrorless cameras, you compose with the LCD or the EVF and then see the corrected view as the designers intended.

That didn’t mean that some of Canon’s lenses didn’t have heavy distortion that required correction. There was, but the image circle fully covered the sensor. You didn’t have to stretch the image to fit the image circle.

What is “Stretching” the Image?

Most people call this distortion correction because these lenses have an extreme amount of barrel distortion. I call it stretching, really, from dealing with Canon patents. With Canon patents, they define the image circle as where they expect acceptable image quality, and that can go for all purposes, completely black.

You can see in this image, with no corrections applied, there’s no image in the extreme corners for the RF 14-35mm. What that logically looks like is something like this image. The rectangle is the sensor, and the circle is the projected image circle imposed on the sensor. As you can see, the image circle doesn’t quite reach far enough into the corners.

To compensate for this, you need to correct for distortion and “stretch” the image out in the corners to fit the entire frame by correcting the distortion, which stretches the image back into the corners.

Why Do They Do This?

Many of the patent applications that I share and talk about mention that the designers are faced with the goal of coming up with smaller designs that are optically good to excellent in performance. Something must give, and if software manipulation gets the result, then the designers choose that.

A smaller image circle allows the designer to make the lens and the elements smaller, especially for lenses of a wider angle of view. An extreme example of this is comparing the size of APS-C lenses with a much smaller image circle to a full-frame lens with a much larger image circle. The APS-C lens is invariably smaller, lighter, and most of the time, less expensive as well.

This also allows the designers to focus on other aspects of the lens’s optical design, including resolution and the slew of aberrations that the designers have to worry about. It’s all a juggling act, and removing the image circle from the equation removes one balancing factor that the designers have to worry about.

So, in Canon’s defense, this allows them to produce lenses that are smaller, lighter, and at times, less expensive than if they didn’t take that compromise.

This isn’t new either, Panasonic and Olympus were doing this in the m43 mount well before Canon even considered it in the RF mount.

Is It Really That Big of a Deal

Let’s take a look at the MTF50 Results from the Canon RF 14-35mm review and compare them before and after correction. I know the common argument is that you lose resolution by stretching, and yes, this is true; you do.

| No Correction | With Correction | % | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Center | 5110 | 5093 | .33% |

| Near Center | 4816 | 4536 | 5.81% |

| Border | 4273 | 4011 | 6.13% |

| Extreme | 4150 | 3708 | 10.65% |

As you can see, as you move further away from the center, your resolution loss increases. To be fair to the Canon RF 14-35mm f/4L IS USM lens used in this example, even with 3700 lp per sensor height, that’s an exceptional result for an ultra-wide zoom lens.

But how does that compare against a lens that didn’t do as much software correction? I had to go digging for a comparative test of a lens that didn’t require the amount of distortion correction that this lens did, and decided the closest example would be the Canon RF 15-35mm f/2.8L IS USM, which is Canon’s premier ultra-wide angle.

At 14mm, the Canon RF 15-35mm f/2.8L IS USM has a barrel distortion of -2.81% versus the Canon RF 14-35mm f/4L IS USM’s rather extreme -5.33%. The RF 14-35 relies on stretching as the raw image has an 8.4EV vignette in the corner (basically black), whereas the RF 15-35mm has a heavy vignette at 4.57EV but isn’t completely black.

We couldn’t compare the line pairs/image height directly because OpticalLimits tested with two different sensor resolutions (30MP versus 45MP). So I decided to look at these two lenses. I really wanted to see how the MTF degraded from the center to the corner. The 14-35 had to use software correction, which results in a loss of resolution, but is the final result still acceptable?

From left to right, the MTF performance is from center to corner. I’ve equalized out the line pairs per image height to match at the center and used that same ratio out to the corner. Perhaps very imperfectly, but I wanted to illustrate how both of these lenses perform in relation to center performance.

Higher is better resolution on the chart, and if you assumed the red line was the 15-35, well, you’d be wrong. The 14-35 is the red line, and the 15-35mm is the blue line.

I’m not stating this as to suggest that the 14-35 is a better lens than the 15-35, there are other factors such as this being wide open on both lenses, and the 15-35mm is one stop faster at f/2.8 versus f/4.0 – but to illustrate that even with digital corrections the resolution loss of the 14-35’s isn’t as extreme as you would lead yourself to believe if this was biasing your decision.

This level of optical performance is what Canon designed the lens to have, and the corrections were factored into that equation to give the final result. And even Klaus, who isn’t a fan of digital corrections, concluded this about the lens.

The Canon RF 14-35mm f/4 L USM IS is one of the best ultra-wide zoom lenses that we have tested to date. And that’s quite an achievement given that the focal length range starts at 14mm. The image sharpness is consistently high across the zoom range with only a slight drop at 35mm f/4. Distortion correction does come at a cost at the 14mm setting, but even so, the results remain impressive. Speaking of autocorrection, the lens relies heavily on the vignetting and distortion compensation, but that’s not unusual in this lens class.

https://opticallimits.com/canon/canon-rf/canon-rf-14-35mm-f-4-l-usm-is-review/

Why Canon isn’t going to Change

At this point, this should be relatively obvious, but to really state this, the image quality loss isn’t that extreme when compared to the flexibility it gives the optical designers. It doesn’t mean that your $1500 lens can be bought for $500 now, because of this, it’s not going to dramatically decrease prices, and nor should you assume that an expensive lens doesn’t use digital corrections.

Canon can and will decide to use digital corrections to compensate for a variety of design constraints, such as size, weight, or cost. The constraint isn’t just cost, and it shouldn’t be assumed so.

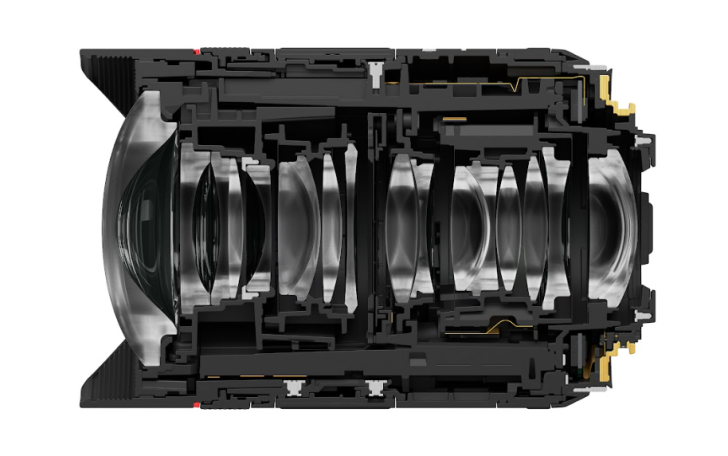

A good example of this is the new Canon RF 14mm f/1.4L VCM, which uses digital corrections and is a very expensive prime. But the elements packed into that 14mm lens are one of the most complex primes in existence, and the lens itself strictly controls aberrations and has impressive resolution across its entire field of view. The designers in this case were using digital corrections to keep the size and weight reasonable, but the lens itself is still a considerably complex lens design.

So it really means that Canon has another tool it can use to come up with lenses that are excellent in their performance, or also lenses that have incredible value for the price of the lens.

Closing Thoughts

Bluntly put, if the lens is bad, it will be bad with or without digital correction, but not because of it. If the lens is good, it will still be good even with digital corrections.

Yes, you do take a resolution loss, especially in the deep corners, by having to digitally correct the final image. But realistically, it’s a gradual degradation that, unless you are working in very specific use cases, you simply are not going to see the loss in the real world.

The only time you really see a resolution loss that visually reaches out and slaps you across the side of the head is when it falls off a cliff into the corner. That’s simply not going to happen because of digital correction; that’s just a bad lens. That’s when you break out DLO and pray for a miracle.

Will I still complain about patent applications that rely on it? Absolutely! Just like I complain about the EOS R100 at every chance I get because it’s what I do.

Go to discussion…

creditSource link